Wacław Tuwalski

|

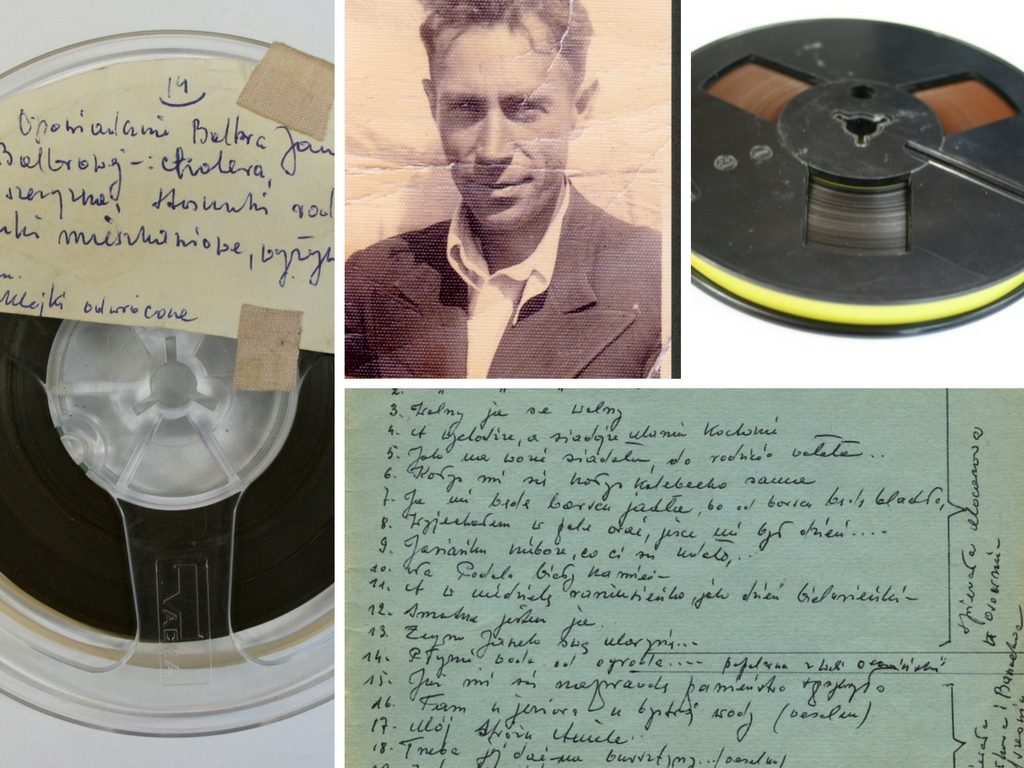

Collecting folklore and, keeping up with advances in technology, recording it in sound and vision, has either been associated with the ‘big names’, e.g. Oskar Kolberg, Gustaw Gizewiusz and the Reverend Skierkowski, or with collective initiatives, such as the Ogólnopolska Akcja Zbierania Folkloru Muzycznego (National Campaign for Collecting Folk Music). However, there are numerous individuals, passionate about folklore in all its manifestations, who can be found all around the country or even scattered amongst single localities. These people are often highly-esteemed in their own communities yet completely unknown in a wider musical world.  Sound carriers and transcriptions from Wacław Tuwalski’s collection. Photo by E Grygier. Photo from the Phonographic Collection of the Institute of Art, Polish Academy of Sciences. Local enthusiasts, researchers and collectors of folkloreThe group of local enthusiasts and collectors is quite substantial and varied. There are both people involved in local cultural institutions (schools, community centres or museums) and individuals who document folklore because they are emotionally attached to it and do it on their own initiative. The Reverend Władysław Skierkowski was one of the most celebrated individuals who loved to document folklore, in his case the region of Kurpiowszczyzna (Kurpie). The works he collected, and published in Puszcza kurpiowska w pieśni (The Kurpie Primeval Forest in Song), were later used by such eminent artists as Karol Szymanowski, Witold Lutosławski and Tadeusz Sygietyński.

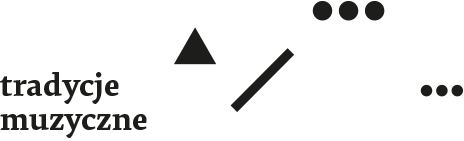

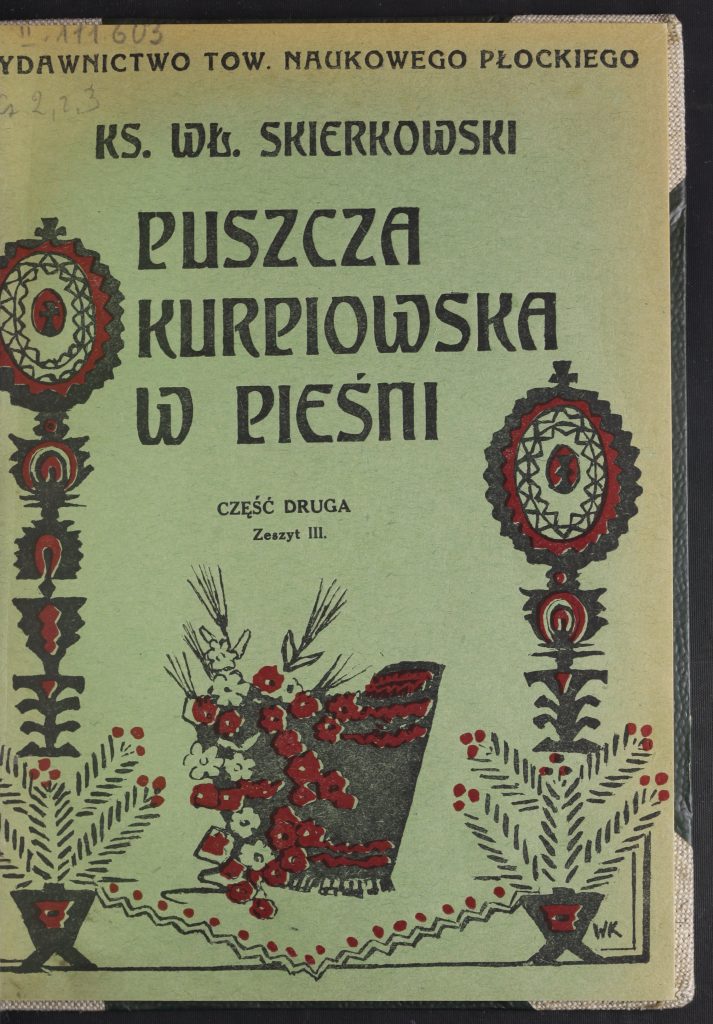

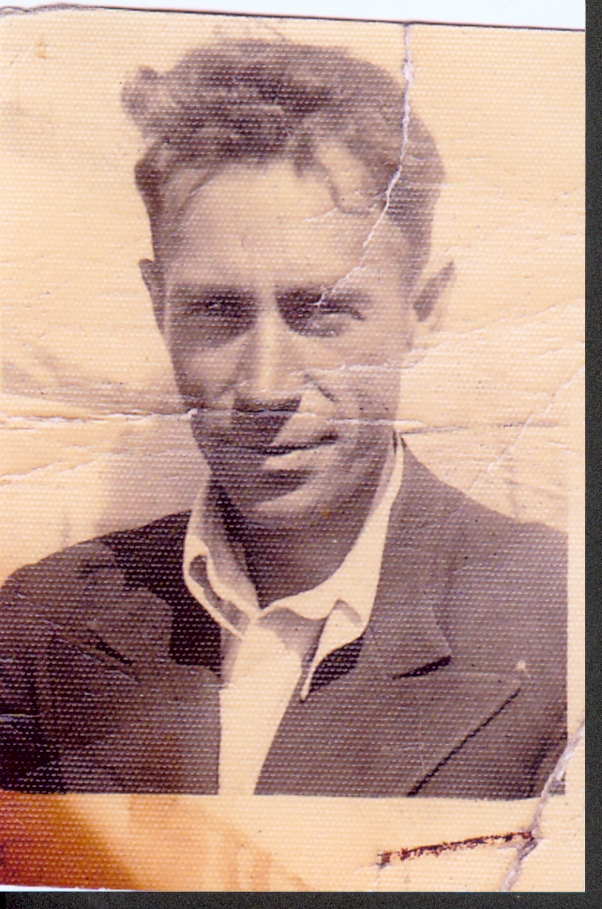

Władysław Skierkowski (1886-1941), Puszcza Kurpiowska w pieśni (The Kurpie Primeval Forest in Song). Volume 2 (out of 3). Source: Polona. The evangelical pastor Gustaw Herman Marcin Gizewiusz was another cleric interested in local folklore, that of the region of Mazury (Masuria). His collections were published as Pieśni ludu znad górnej Drwęcy w parafiach ostródzkiej i kraplewskiej zbierane w 1836 do 1840 roku (The Songs of the People from the Upper Drwęca in the Parishes of Ostróda and Kraplewo Collected between 1836 and 1840). Such collections are sometimes destined to lie in obscurity waiting to be discovered, as in the case of the wax cylinder recordings made by Juliusz Zborowski – director of the Tatra Museum (Muzeum Tatrzańskie) in Zakopane. Zborowski documented the music of the Tatra Highlanders in 1913 and 1914. The recordings lay in the cupboards of the museum up until the twenty-first century, when they were finally digitalised and released on compact disc.  Rozpoczął tedy fonograf zbieranie melodii podhalańskich… (And then the phonograph began to collect the Tatra tunes…) From the Phonographic Collection of the Institute of Art, Polish Academy of Sciences. Wacław TuwalskiWacław Tuwalski is one of the lesser-known collectors of local traditions. All his life and work were squarely focused on the small village of Wola Osowińska in Ziemia Łukowska (Łuków Land), Borki Commune, Radczyński Poviat, Lubelskie Voivodeship. The village is currently occupied by under a thousand inhabitants. However, Wacław Tuwalski did not originally come from Wola Osowińska. He was born on 18 September 1909 in Pogorzel, eight kilometres from the town of Mińsk Mazowiecki (he did die in Wola Osowińska though, on 19 March 1995). He was born into a poor peasant family. His main preoccupation when he was a child was grazing cows. After completing primary school, he decided to continue his education at the Państwowe Męskie Seminarium Nauczycielskie (State Teacher Training College for Men) in Siennica, where he studied between 1923 and 1928. After the Second World War, he enrolled on the Institute of Social and Economic Studies of the Rural Areas at the Catholic University of Lublin, where he graduated after two years. His comprehensive education in Siennica had taught him to read and write music and to play the violin (all of which he used extensively during his further teaching career).  Wacław Tuwalski, a photo from the collection of the Regional Museum in Wola Osowińska. From 1928, Tuwalski worked as a teacher (since 1932 in Wola Osowińska). He taught a whole range of subjects, including natural sciences, drawing and, even, physical education. He was the originator of the first Health Cooperative (Spółdzielnia Zdrowia) in Lubelskie Voivodeship, which he established in Wola Osowińska in 1956, and a new school building. The old school thus became the regional chamber and branch of the Regional Society (Towarzystwo Regionalne), funded by Tuwalski in 1977, which today is named after him as the Muzeum Regionalne w Woli Osowińskiej im. Wacława Tuwalskiego (Wacław Tuwalski Regional Museum in Wola Osowińska). Here are some of the objectives that Tuwalski stated whilst serving as president of the Regional Society: „continue collecting all the elements of art. These are the last years when we can still save some things that have not been yet lost. 2. Organise folk ensembles in all the domains of art. 3. Promote active participation in artistic creativity. 4. Expand collecting exhibits into outlying villages. 5. Keep on providing assistance and support for folk artists. 6. Introduce elements of folk art into our homes, schools, streets and village fairs and festivities” (W Tuwalski, Kultura Ludowa. Program rozwoju Towarzystwa Regionalnego i Wsi Wola Osowińska [Folk Culture. A programme of further development of the Regional Society and the Village of Wola Osowińska], ed. President of the Regional Society in Wola Osowińska Wacław Tuwalski, brochure, date unknown, judging from the contents it was published in 1990, p. 19.) Documenting the folklore of Wola OsowińskaAlthough Tuwalski was not a native inhabitant of Wola Osowińska, he devoted all his professional life and much of his free time to that village. After his school work, Tuwalski wandered around the area (occasionally on a bicycle) and documented its material and non-material legacy: he collected traditional elements of house furnishings, tools and folk costumes. But what is particularly important from our point of view is that he also documented the local folk music. Initially, he used the so-called pencil method for his documentation purposes. He took down his wedding notes back in 1935-1938 usually recruiting his informants from amongst elderly women. Unfortunately, those notes were lost during the ravages of the Second World War. He did not introduce voice recordings after the war, most probably in the 1960s. He attached a tape recorder to the carrier of his bicycle and thus reached the farthest corners of Wola Osowińska, Osowno and the other neighbouring villages.  Wacław Tuwalski’s home in Wola Osowińska, photo by J Jackowski. Photo from the Phonographic Collection of the Institute of Art, Polish Academy of Sciences. He made huge efforts to promote the local artists. One of his initiatives was to gather and publish a collection of poems titled Wiersze spod strzechy (Poems from under the Thatched Roof) written by the local folk poet Teodozja Wierzchowska from the village of Sętki. Today, Wola Osowińska hosts the Międzywojewódzki Konkurs Recytatorski Poezji i Prozy Ludowej im. Wacława Tuwalskiego (Wacław Tuwalski Inter-Voivodeship Folk Poetry and Prose Recitation Competition). RecordingsTuwalski left behind numerous recordings made on reel tapes and cassettes. The recordings are now owned by the Regional Museum and their digitalised copies are also kept in the Phonographic Collection of the Institute of Art at the Polish Academy of Sciences. The collection includes ethnographic recordings, e.g. interviews about the local history, stories, information about herbal medicines and traditional healing methods, as well as ethnomusical recordings, such as wedding songs, funeral songs and other types of ceremonial and everyday rural repertoire.  A tape from Wacław Tuwalski’s collection, photo by E Grygier. Photo from the Phonographic Collection of the Institute of Art, Polish Academy of Sciences: Ethnomusical recordings:

Ethnographic recordings – ethnographic interviews

What is sorely lacking in Tuwalski’s recordings, however, is instrumental music. Tuwalski mostly documented elderly female singers and vocal ensembles. There are performances of the mandolin ensemble that he himself directed (recordings of its individual members), but they do not contain folk music. The local area could actually boast an instrumental ensemble established by the Mateusiak family but for some reason Tuwalski omitted it. A wedding in Wola Osowińska as noted down by Wacław Tuwalski The notes concerning the rituals and repertoire performed at weddings that Tuwalski took down in the 1930s were sadly, and typically, lost during the ravages of the Second World War. It is worth noting here that Tuwalski was a member of the Bataliony Chłopskie (Farmers’ Battalions), a rural underground movement fighting against the German occupiers, and held false identification papers issued in the name of Józef Kurecki. He succeeded in restoring the notes from memory after the war, however. A description of a wedding as portrayed by Tuwalski falls into ten stages:

A wedding ceremony was recreated and filmed in accordance with these instructions. Unfortunately, the video version is not easily available, but I strongly recommend that anyone interested in watching it visit the Regional Museum in Wola Osowińska. EndingIt is not often the case that a small community has been graced with its ‘own’ regionalist. Located at the crossroads of three regions: Mazowsze (Mazovia), Podlasie (Podlachia) and Lubelszczyzna (Lublin Land), Wola Osowińska has been a lucky exception, though. Today, thanks to the hard work of the local teacher, Wacław Tuwalski, the recordings of traditional folklore bring us closer to the type of repertoire that was performed in the area in the past eras. The attitude of Tuwalski, who spared no expense of time and money to document the folklore, is worth the utmost admiration. He did not only collect the ‘folk miscellany’ (including songs), but also strived to recreate the local folk costumes and directed performances (e.g. weddings). His contribution to the preservation of the material and spiritual culture of Wola Osowińska cannot be overstated. |