Let’s go dancing!

|

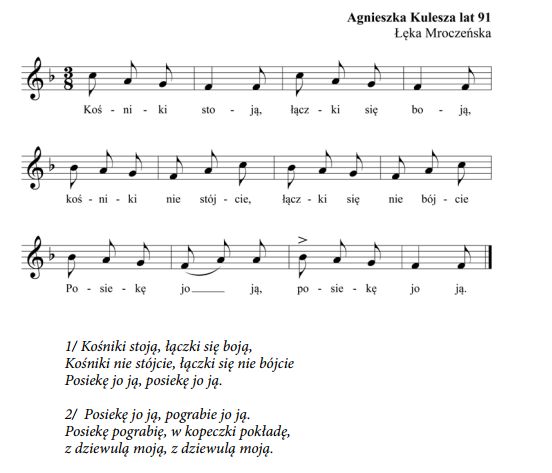

Oberek, polonaise, kujawiak – these are all household names in Poland, even if not everyone knows how to dance these dances. On the other hand, miotlarz, szot, stara baba or brutczi tunc probably sound familiar only to a select few. What is ślo foks? Was it danced in rural Poland? Celebrated in late April, International Dance Day is a perfect opportunity to find out about these and other lesser-known Polish folk dances. Let us begin with ceglorz from Wielkopolska (Greater Poland): Traditional dancingTraditionally, dancing was chiefly seen in the rural parts of Poland as organised entertainment and an occasion to celebrate certain annual and familial rituals and customs. The wedding ceremony of oczepiny in the region of Kashubia (Kaszuby) included the so-called brutczi tunc, symbolising the end of maidenhood, danced mainly by the bride to the rhythm of polka or quick waltz (walczyk). It starts with the bride dancing with the local governor, her father and father-in-law and only later with the bridegroom, who shows her around the chamber and goes on to dance with bridesmaids and other maids. The last dance, however, is taken up by the groom and the bride again. The ceremony proper commenced after the dances, which were themselves only dedicated to a select group of dancers. The same applies to certain annual rituals, such as taniec na wysoki len (‘high flax dance’) or taniec na konopie (‘hemp dance’), which were only performed by older unmarried women, as well as matrimonial dances for young men during Kupała Night.  A group of folk dancers during a harvest festival, 1934, Głębokie. Source: NAC. Dancing was not only the domain of rituals, though. There were regular dance parties, too, which were simply intended for pleasure and entertainment. If no musicians resided in the village, they were brought in from outside. Normally, the villagers were enthusiastic dancers and they did not wait for a special invitation to hold a dancing event, but it was not always possible. Because of the high farming season, dancing was restricted in spring, and in the summer, in times of drought, people would say: susa – to bida, nie trza tańcować [drought makes people poor and dance-less] (Katarzyna Dyga, born 1885 in Obryte, in: G. W. Dąbrowska, Dance in Polish Tradition, Lexicon, p. 161). As soon as the harvest season was closed, however, people were ready to dance again. In several regions around the country, e.g. in Wielkopolska (Greater Poland), people celebrated the so-called wyzwalanie kośników (‘releasing a stinkbird’), also known as wyzwalanie wilka (‘releasing a wolf’) or frycowe (‘the price of inexperience’), an occasion for dance parties at village inns. There are numerous songs whose lyrics refer to wyzwalanie kośników celebrations, e.g.:  Józef Majchrzak The Folklore of Kępno Land, 2013, p. 132, see the source. Dance partiesMany dances have a playful character – they may imitate some mundane chores or even some common animals. The dancers often use props, e.g. a broom (in the dance called miotlarz). Żabka or Żabiok (literally ‘a little frog’), in 3/4 or 3/8 time, is danced by men in the region of Kurpie. The name either refers to characteristic frog-like jumping movements or a short refrain chanted during the dance: żab, żab, ża-bu-lin-ka, żabka Mietlarz is danced at social events; as the Polish names suggests it calls for a broom as an accessory. Brooms or sticks were traditionally associated with magical properties. A broom could be used to ward off evil forces: placed by the door, it guarded the house against witches; it could also be brandished as a weapon to keep away evil spirits (Magical traits are also found in zając/zajączek – literally ‘a bunny’). Mietlarz consists of two separate sections. Initially, the dancers stand facing each other in pairs, but there is an odd one out who does not have a partner and therefore gets a broom to dance with (he performs some ‘sweeping’ movements with it). As the first section draws to a close, the broom dancer chucks away his prop and tries to grab one of the female dancers, with whom he dances in the second, fast section, a whirling polka. After the second section has concluded, the dancers return to line and the whole sequence starts again. This time the broom is held by another unpaired dancer. The dance bears numerous other names, such as mietlorz, na mietłe, polka z mietłą (‘polka with a broom’), kostur, kijowy, dziad, dziod, weksel, polka weksel etc.  Dancing at the Mazurkas of the World festival, April 2019, photo by E Grygier City versus VillageThe sheet music sold at village fairs often contained the latest ‘hits’ performed in cities, including new dances, such as foxtrots and slow foxes, also known in Polish villages as ślo fokses. Tangos were also widely popular in rural areas. The repertoire frequently changed to suit the use of different musical instruments. The arrival of the new repertoires coincided with the appearance of accordions and brass instruments. Listen to a slow fox performed by excellent multi-instrumentalist Stefan Nowaczek: Several dances originated abroad. Danced to bagpipe music in Wielkopolska, rajlendler was brought in the nineteenth century by repatriates from Germany. It was called lendler in Mazowsze (Mazovia). Oskar Kolberg described this dance in the following words: The ländler was also very popular in towns up until the beginning of this century. Neither was it shunned by famous composers, such as Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven, who supplied the ländler repertoire aplenty Oskar Kolberg, DWOK, Vol. 62, p. 647. Another foreign dance that won popularity in Wielkopolska was szot, also known as szocz, szorc, siot, siatys or siotys – all of the words being folk derivatives of the German word schottisch. The dance originally came from Scotland and it was also known in France, as anglaise, and in Scandinavia, where people still dance Swedish scotishes. Szot is a binary dance inextricably linked to the following refrain: Zagrajtaż mi szota, szota, niech otrząsnę nogę z błota /Play the szot, the szot for me, Till my legs become mud-free/ Dance studiesThe research into traditional dances in Poland has mostly been conducted by Grażyna Władysława Dąbrowska and, in various respective parts of Poland, by the local investigators, e.g. Alicja Haszak, a folk dance authority in Rzeszowszczyzna (around the city of Rzeszów). Look at how polka z nogi is danced in Rzeszowszczyzna: Tomasz Nowak, a musicologist, has endeavoured to debunk some common myths associated with Polish national dances. He contained his analyses and conclusions in Taniec narodowy w polskim kanonie kultury (National dance in the cultural canon of Poland). Scholars still argue whether and which dances should be classified as traditional, authentic, national or stylised – the concepts and classifications vary in respect to the authors of specific publications and historical contexts. Regional dancesObereks and polkas have been danced throughout Poland, but there is also an abundance of regional varieties of music and dance. The map found at http://www.tance.edu.pl/ provides an excellent account of characteristic regional dances in Poland. The following list shows the most popular dances in Śląsk Cieszyński (Cieszyn Silesia):

Szocz, polka, walcerek and wiwat are widely common in Ziemia Lubuska (Lubusz Land). Around the city of Szamotuły, people enjoy dancing tyrolinka, równy, polka kulawa and wiwat adoracyjny. The area around Pszczyna in the so-called Zielony Śląsk (Green Silesia) is famous for its trojok, waloszek, szkrobok and mamlas dances. As far as dancing is concerned, Warmia is characterised by żabka, puszczany, szewc, kowal, pofajdok and hejduk, but people in nearby Mazury (Masuria) prefer biwat, skoczny, stryjenka and kozioł. In Sieradzkie (around the city of Sieradz), dancers choose bąk, chodzony and polka mazur for their dance-floor exploits, while dżek is danced all around Kashubia (Kaszuby). If you want to dance sztajerek, krzyzok or tramel-polka, you had better head down to Nowy Sącz. In Lubelskie (around the city of Lublin), people revel in powiślok, koło and taniec z korowajem, but if you found yourself in Spisz on the Slovakian border, you would probably have to learn how to dance zbójnicki, mazur spiski or ciardaś śpiski. The list is virtually endless. Sometimes, though, it is best to start ab ovo. How do people dance the oberek, the most popular Polish folk dance? The answer to this and many other questions can be found in the following online video guides prepared by traditional dance specialists:

|