Indigenous peoples and their folklore

|

The day of 9 August is celebrated as the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples. On this occasion, we will have a look at the folklore of the ethnographic, ethnic and national minorities living in Poland as well as the Poles living in other countries. Although Poland is considered a relatively homogenous country with regard to the nationality and religious affiliation of its citizens, some of them declare a dual national and ethnic status. Such a situation is quite common in the province of Silesia (Śląsk), where according to the Statistics Poland (GUS) data of 2011 close to 390,000 people stated dual nationality, and Kashubia (Kaszuby), where a similar status was declared by 214,000 local inhabitants. Dual Polish-Jewish nationality was recorded for close to 5000 people, Polish-Lemko 2600 and Polish-Romani 4500. The National Census of late March 2011 also found that almost 3000 people thought themselves as Polish Highlanders. National and ethnic identification other than Polish was specified by nearly 680,000 people in total, including: – Kashubian (17746) – Kocievian (19) – Lemko (7086) – Masurian (252) – Highlander (96) – Silesian (435750) – Greater Polish (468) – Jewish (2488) In terms of population, Silesian national and ethnic identification comes second after Polish.  Women in traditional clothes, Chorzów. Source: Polona.  Women in traditional clothes, Upper Silesia (Górny Śląsk), photo by H Poddębski. Source: Polona. LemkosThe Lemkos used to populate the area of the Low Beskids (Beskid Niski) and the Bieszczady Mountains. Similar to other Ruthenians – the Boykos and the Hutsuls, they were persecuted after the Second World War and were driven away from their own households. Some of them were forcefully relocated to western and north-western Poland as part of the so-called Operation Vistula in 1947. Lemko music reveals Polish, Slovakian and Ukrainian traits. One of its most characteristic features is the use of polyphonic singing. The earliest type of Lemko ensemble consisted of a fiddler and a bass fiddle player, who were later augmented by a second fiddler playing either a third part (kontra) or doubling the first fiddle (husli). Interesting samples of Lemko music, including instrumental pieces, can be found on a CD album released by Polish Radio, Mniejszości narodowe i etniczne w Polsce cz. I (National and Ethnic Minorities in Poland Part 1).  Girls in Lemko costumes, Komańcza. Source: Polona. BorderlandThe borderland is an exceptionally fascinating part of the country as far as different nationalities are concerned. It is a mixture of languages and cultures, and people often describe themselves simply as ‘local’, e.g. the Belarusians from the province of Podlasie (Podlachia) often characterise themselves as ‘Orthodox local’. The region itself is an immensely exciting ethno-musical area inhabited by Poles, Ukrainians, Belarusians (the last two differing from the native Poles not only because of their languages but also their Orthodox Christian faith) and formerly also Jews. The people often sing in the so-called gwara chachłacka (a Podlachian microlanguage). It exhibits a mixture of Ukrainian, Belarusian and Polish elements, and basically exists only in the spoken (oral) form. Originally, the designation Chachły (Khokhols) was commonly used as a Russian slur for the Ukrainians. There are some interesting bilingual songs that still exist in Masuria (Mazury). In the past, the area absorbed both Polish and German idioms and these two languages are needed to understand the songs. Anna Lorkowska (born in 1906 in Nowa Kaletka, Olsztyński Poviat, who lived in the village of Przykop) sang the song called Nasz parobek unser Knecht zabił pieska das war recht

Nasz parobek unser Knecht / Our farmhand unser Knecht zabił pieska das war recht / killed a dog das war recht Na kamieniu auf den Stein / On the stone auf den Stein Kele wodi Wasser lein / Near the water Wasser lein

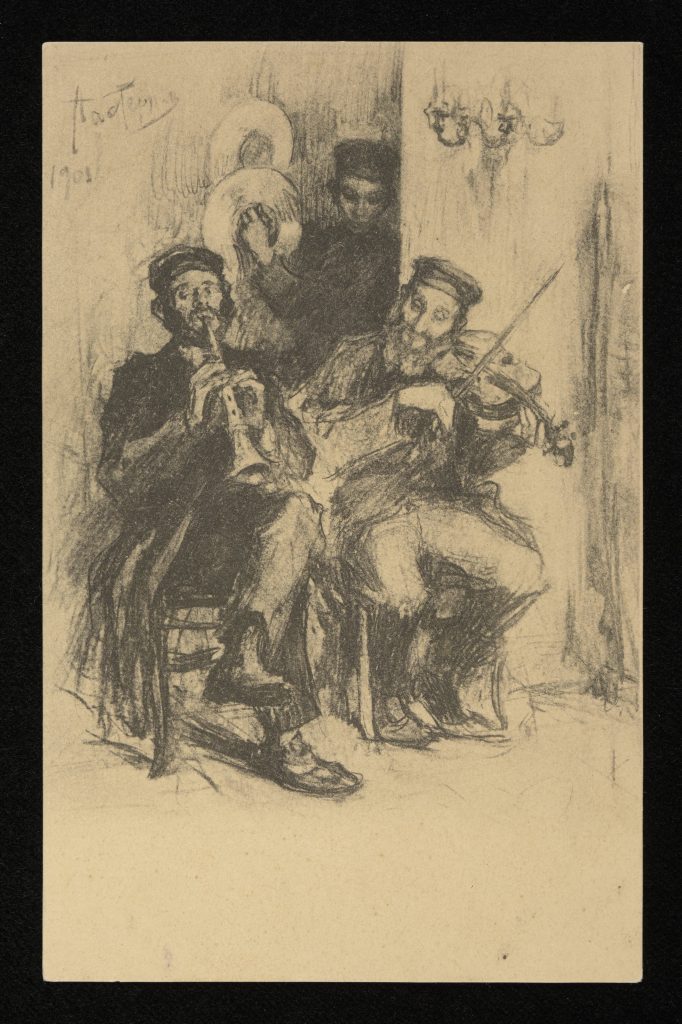

JewsBefore the Second World War, Jews made up 10% of all the citizens of Poland, which roughly amounted to 3 – 3.5 million people. At that time, the Jewish folklore was diligently documented by Menachem Kipnis, but sadly his collection was later destroyed during the war. Post-war recordings are scarce. The Phonographic Collection of the Institute of Art, Polish Academy of Sciences houses recordings with a Jewish-born violinist, Barbara Wolfowicz. Polish Radio (Polskie Radio) is in the possession of materials featuring Majer Bogdański from Piotrków Trybunalski. However, the artist did not learn to play until after the war when he was eager to perform folk music saved in memory.  Jewish musicians, source: Polona. Worth mentioning here are publications by Michael Aylward, who was an enthusiast of Jewish music, including the repertoire performed in Poland before the Second World War. I wrote about the interrelationships between Jewish folklore and Polish folklore in one of my earlier essays. Today, Jewish types of polka, such as żydóweczka and szabasówka, can only be heard in the repertoire of native Polish musicians. Poles abroadWhen discussing minorities, we must not forget about the large Polish diaspora abroad. What can we say about Polish folklore practised in other countries? Extensive ethnomusicological studies relating to the topic have been conducted in the academic and scholarly centre in the city of Poznań (notably represented by Prof. Bożena Muszkalska, Łukasz Smoluch and formerly also Prof. Jan Stęszewski). Polish Radio has released several CD albums dedicated to the Polish diaspora in Kazakhstan, Romania, Ukraine, Brazil and Argentina.  A flier from the 1930s (‘Board a Polish Ship to South America’). Source: Polona. Our fellow Polish countrymen first arrived in South America in the late nineteenth century. The bulk of them came from the northern part of the Polish province of Mazowsze (Mazovia). There were so many of them that the whole period was dubbed the ‘Brazilian fever’ (‘gorączka brazylijska’). The theme of Polish emigration to South America was extremely popular in the inter-war period too.  Source: Polona. As Prof. Piotr Dahlig points out, Polish music recorded in Argentina and Brazil often resembles the domestic Polish repertoire. The main difference, however, lies in the fact that the tempo of the tunes seems to be demonstrably slower, although it is hard to say whether it indicates the original tempo used in the nineteenth century or an evolutionary step developed in South America. I warmly recommend listening to a CD released by Polish Radio (Polskie Radio), which contains music performed by Polish-Brazilian conjunta (ensembles).  A CD album from the series ‘Muzyka Źródeł’ (‘Sources of Polish Folk Music’) with folk music of the Polish expatriates. Poles do not only live in South America – they form quite a sizeable diaspora in North America as well. There are numerous archival recordings of Polish folk artists from the Chicago area, where most of the Polish Americans come from. Especially intriguing is the phenomenon of the so-called polka chicagowska (‘Chicago polka’), a topic I will pick up in my next essay. In the meantime, you may want to enjoy watching the comedy The Polka King to gain some contextual knowledge. |