Pilgrims’ Songs

|

Late July marks the beginning of the season for walking pilgrimages to the centres of worship, where famous revelations and miracles once occurred. This year, the longest pilgrimage in Poland will connect the town of Hel in the northernmost part of the country and Częstochowa to the south. In the space of close to twenty days, the travelling and singing pilgrims will cover the distance of 640 kilometres. Pilgrimages have a rich and long tradition in Poland. Today we will discuss the pilgrims’ repertoire and the image of the pilgrim in popular folk culture.  A pilgrim in prayer, photo by an unknown author, 1939, source: Polona

Sacred songsA considerable part of the traditional Polish folklore is inextricably linked to the liturgical calendar of the Catholic Church. The religious festivals – Christmas and Easter – are an occasion for performance of carols and pastoral songs. In May – the month dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary in the Catholic Church, people gather by the wayside shrines to sing Marian songs. In June, folk traditions abound in the Corpus Christi processions. Yet when Lent arrives, village music dies down. Worth pointing out is the fact that in Poland sacred folk songs are not only sung by the Catholics. The members of the Orthodox and Protestant Churches join in the celebrations as well. Numerous saints have their special place in folk tradition: they are mentioned in proverbs, sayings, tales and songs. Patron saints are frequently used as ‘road signs’. Kolberg informs us that in the south of Poland (Tarnów Land and Rzeszów Land), beginning on 29 June, „the ears of corn whiten” by „being lit up from the roots by Saints Peter and Paul” (Oskar Kolberg’s Complete Works, Vol. 48, p. 82). Almost a month later, on 25 July, „after Saint James’ Day, everybody’s picking their pots (because the harvest time is over)” (Oskar Kolberg’s Complete Works, Vol. 48, p. 83). There is a legend about how Jesus was travelling with the Apostles:

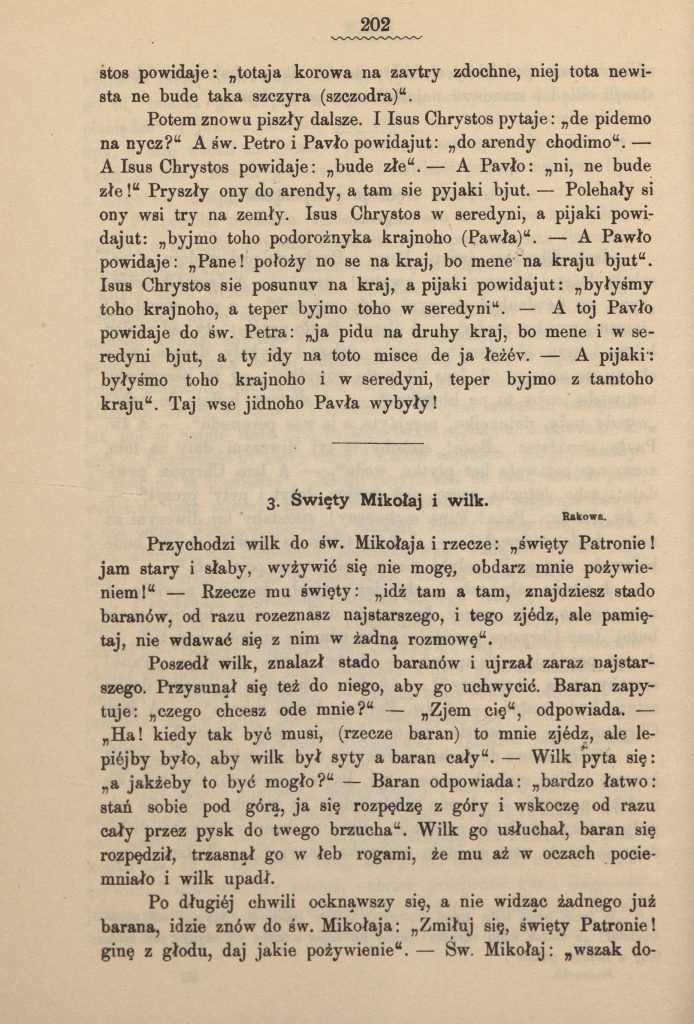

Oskar Kolberg, Oskar Kolberg’s Complete Works. Przemyśl Land Vol. 35 pp. 201-202, source: Polona. Pilgrimages and pilgrims The pilgrimage phenomenon has a long tradition dating back to Ancient Egypt, Rome, Greece and other historic civilisations. “Pilgrimages are journeys to sacred places that commemorate the Saviour and the Lord’s Saints in order to give them tribute and ask for succour in spiritual and earthly affairs” wrote an anonymous author at the turn of the twentieth century in: Anonymous, Zbiór pieśni i modlitw używanych w nabożeństwach i pielgrzymkach (A Collection of Songs and Prayers Used in Liturgy and Pilgrimage), 1914, p. 5.  A stone pilgrim near Nowa Słupia, Stefan Plater-Zyberk, 1932. Source: Polona. The most famous pilgrimage destinations in Poland are Jasna Góra, Łagiewniki, Licheń and Ostra Brama. However, people often make pilgrimages to lesser known sanctuaries and Calvaries, such as Kodeń, Kalwaria Pacławska and, in particular, respective local centres of worship. In Lubelskie (Lublin Land), the pilgrims usually travel to Wąwolnica, Kodeń, Janów Lubelski and Leśna.  Picture: Obraz N. Maryi P. Częstochowskiey (Our Lady of Częstochowa), engraving, unknown author, source: Polona At the end of the sowing season, both in spring and autumn, people make pious journeys to the places famed for their graces and miracles, in particular to Częstochowa, Leśna, Kodeń etc. They call this pilgrimage, lasting from several to more than a dozen days, indulgence. They mostly travel on foot stopping by every wayside cross, statue or shrine to kneel down, circle it on their knees and kiss it upon departure. When they finally reach their destination, they listen attentively to the words of the service, make a confession and, wherever possible, circle the grand altar and the whole church on their knees. Then they give alms to the poor, buy holy medals, prayer beads, pictures and rings for their relatives and children, offer a Mass and return home, yet this time they do not circle the crosses on their knees but only kneel down in front of them in adoration. Oskar Kolberg, Oskar Kolberg’s Complete Works, Vol. 33, Chełm Land, p. 156.

Indulgence in Kalwaria Zebrzydowska, unknown photographer, source: Polona  Indulgence in Kalwaria Zebrzydowska, unknown photographer, source: Polona During their pilgrimages, the peasants often adorned the crosses and shrines they passed with colourful beads, towels and aprons. The beads were often hung around the neck of the Blessed Virgin Mary or attached to the birettas and habits of the saints. A pilgrimage would often be accompanied by an elderly lyrist. In the following passage, Władysław Reymont colourfully recounts meeting lyrists on his pilgrimage: It is a showcase of the ugly and the horrible. They sit on both sides of the passage. I counted as many as thirty-two blind, lame, dumb and gnarled types of people. By the way they hold out their hands and point out to their various disabilities you can easily tell that they are seasoned professionals. When they beg, they produce incredible sounds, twist their bodies, lie flat on the ground and whine for a penny from their pious brothers and sisters, while each one of them vows to be the most wounded and miserable. It is a veritable plethora of human types, movements, whinnies, beards, sighs, apostolic looks and scoundrel faces – a dump of despicable souls: it is easy to tell that the begging is only superficial and underneath that masquerade there is obnoxious cynicism and duplicity of professional crooks. There is only one man in this horror show that looks genuine. His blindness is not fake and he sings incessantly. There is an old woman beside him singing along in a falsetto. I sat behind the pair to listen to what they were singing. As the crowds exiting the church were wearing thin, my old beggar sang the following lyrics: Władysław Reymont, Pielgrzymka do Jasnej Góry (Pilgrimage to Jasna Góra), pp. 82–83. Reymont saw the presence of the beggars as something distasteful, although he did listen attentively to the pious songs performed by one of the old lyrists. The symbolism of the wandering elderly lyrists in the context of pilgrimage is extremely important. In folk culture, the old beggar was chiefly associated with ancestors and the dead. Old beggars were men of the road, they usually travelled away from home and so they were always viewed as newcomers, strangers and, because they wandered from church fete to church fete with a stick and a bag on their shoulders, as pilgrims (close to the Church and God). Similar to the man himself, the instrument on which he often played, the hurdy-gurdy, was also interpreted in multiple ways. Songs sung on the road The repertoire performed by the pilgrims has existed in two mediums: oral and written. Sacred songs of pilgrimage can be found in the collection of the Ethnolinguistic Archive of the Maria Curie Skłodowska University (UMCS) in Lublin and the Archive of Sacred Folk Music of the John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin (KUL). „Picture the most beautiful example of a young pilgrim, Jesus Christ, on the road to Jerusalem. A modest and calm young man, God’s son, makes a journey with a passionate desire for glory and adoration of his heavenly Father singing psalms on his way (…) The songs and conversations are interspersed with common prayers of the rosary, litanies etc. performed for various intentions (…)” Practical instructions for pilgrims, in: Anonymous, Zbiór pieśni i modlitw używanych w nabożeństwach i pielgrzymkach (A Collection of Songs and Prayers Used in Liturgy and Pilgrimage), 1914, p. 9. Władysław Reymont colourfully described pilgrims’ songs, pointing out that several different songs were sometimes sung simultaneously, in the following passage: An older brother intones another one but at the same time there resound at least a dozen other songs with different melodies. It is now clear that this huge body does not have a single centre: rather there are a dozen centres; you can see hundreds of groups, clustered together by parish, village or even district, and there is always someone who leads the others holding a book and intoning a new song. The result is such a cacophony, such an awful commotion that one can barely hear anything; the lamentation of these voices creates a horrible whirl which beats against my ears without mercy, like a piercing and hoarse clatter Władysław Reymont, Pielgrzymka do Jasnej Góry (Pilgrimage to Jasna Góra) pp. 9–10. Pilgrimages are therefore not only rites of passage and developed states of communitas (more in Barbara Śnieżek), but also an interesting acoustic phenomenon, which today, with the extended knowledge of constructs such as soundscapes and acoustic ecology pioneered by Canadian scholar and composer Murray Schafer, can be referred to as schizophonia. On the one hand, pilgrims’ songs are essentially a religious repertoire, which can also be transferred to extra-pilgrimage contexts. On the other hand, pilgrimages produce songs that are associated with specific places of worship. Pilgrims’ songs usually contain multiple verses. There may even be as many as fifty verses of a song sung on a pilgrimage. The pilgrimage repertoire consists of several different genres:

From: Stanisława Niebrzegowska-Bartmińska, Pieśni pielgrzymkowe (Pilgrims’ Songs), in: Lubelskie, Polska Pieśń i Muzyka Ludowa (Lublin Land, Polish Song and Folk Music), Part III, pp. 592-593. Pieśń do Matki Boskiej Gidelskiej (Song to Our Lady of Gidle): Oh Our Lady of Gidle, archangel queen, He looked to the right, And saw a picture and a crown Oskar Kolberg, Oskar Kolberg’s Complete Works, Vol. 45, p. 317 Pieśń do Matki Boskiej Leśniańskiej (Song to Our Lady of Leśna):

You are, oh Lady, praised by thy people. Weave, oh maidens, rosy wreaths For Our Lady of Leśna. Hail, hail, hail, Hail, Mary

Because you loved the people of Podlasie. Weave, oh maidens, rosy wreaths For Our Lady of Leśna. Hail, hail, hail, Hail, Mary

Pilgrims come from near and far. Weave, oh maidens, rosy wreaths For Our Lady of Leśna. Hail, hail, hail, Hail, Mary

To seek succour or else we perish Weave, oh maidens, rosy wreaths For Our Lady of Leśna. Hail, hail, hail, Hail, Mary in: Lubelskie, Polska Pieśń i Muzyka Ludowa (Lublin Land, Polish Song and Folk Music), Part III, p. 603. Song Żegnamy cię, Jasna Góro (Farewell to Jasna Góra): Farewell, Jasna Góra, oh imposing monastery, Maybe it’s the last time that my feet have carried me here. Bless us, oh Mary, our beloved Virgin, Bless us, oh Queen, Our Lady of Częstochowa. in: Lubelskie, Polska Pieśń i Muzyka Ludowa (Lublin Land, Polish Song and Folk Music), Part III, p. 622.

Our Lady of Gidle, engraving, copperplate, unknown author, before 1800. Source: Polona. An interesting reversal of the pilgrimage situation, mentioned by Stanisława Niebrzegowska-Bartmińska in the volume about Lubelskie (Lublin Land) from her Polska Pieśń i Muzyka Ludowa (Polish Song and Folk Music), is a peregrination of the painting of Our Lady of Częstochowa. There, it is the Blessed Virgin Mary who comes to visit her people rather than the other way round. The so-called pieśni śpiewane za obrazem (songs sung behind the painting) were frequently borrowed from the repertoire of the people pilgrimaging to sacred places. |